I’ve been on a year-long coming-to-terms with capacity, as a concept.

Here’s what happened: At the beginning of last year, I sat down with a calendar and blithely booked trips and visits from mid-March through mid-July. Over an 18-week period, I committed myself for 14 weekends, including two international trips. Cumulatively, I spent five and a half weeks away from home, and that’s not accounting for the time spent hosting guests.

At the time, I thought it was a good idea.

In fact, at the time, I thought it was brilliant. I thought I was a master-scheduler. I envisioned rolling through the months ahead, racking up triumphs like Mario collecting coins, pounding mushrooms, launching from turbo boost to turbo boost. Boy, the good times: were they going to roll.

By the time my first international trip hit in April—a combined work/vacation to the UK which I’d hoped to extend by taking as few PTO days as possible—my mood had shifted from anticipation to dread. Seeing people was great, but the interim stress drove me down a manic spiral.

I convinced myself that my only way out was to double-down on creative commitments. I developed a punishing schedule that would involve writing something in the neighborhood of 20–30 hours a week on top of my full-time job. For about two weeks, I told this plan to everyone I met. I journaled about it obsessively. One of the friends I visited on my trip heard me deliver a detailed outline of this plan on no less than three separate occasions. I watched eyes glaze over mid-monologue and couldn’t help myself. The plan was urgent. Essential. It was my way out.

Then I returned home, and my ability to do anything pancaked. My over-booked schedule crowded out every other meaningful, fulfilling interest I had. I stopped trying new recipes, I stopped reading, I stopped writing. And then the guilt over not doing these things began to mount. I’d assemble a schedule for myself to accomplish these things, and then the moment to accomplish them would arrive, and I’d binge the silliest Netflix show I could find.

The release valve came as more of a slow leak. My schedule eased. Obligations rolled off. I started to say no to new plans. I implemented a “no two weekends in a row” rule. For the first time since my move to Chicago, I started turning down visitors.

My calendar newly free, I began to fill it with projects. The largest and most substantive was a quilt that I had begun four years previously, offered to a friend in exchange for a pair of hand-knit sweaters. I began to view it as the final boss fight of the year: 2024 was already so irrevocably overwhelming, the least I could do was clear every possible obligation so that nothing would haunt me into 2025.

Originally, I imagined myself completing the quilt project before an October trip home. Then the goal became Thanksgiving. As a desperate final measure, I brought it with me on the train home for Christmas. I quilted through the entire holiday, sometimes late into the night, determined not to bring the project back to Chicago with me. I delivered it mere hours before my train was scheduled to leave.

Finally, lesson learned, I spent two days reading in bed. I went to IKEA to assemble a new bookshelf. I grew inspired. I wrote down a new January schedule, determined to start the new year dedicated to my own creative work. No more intrusions.

Two weeks later I redecorated my bathroom. I ripped the old vanity mirror off the wall, discovered the cavity it had been covering from the previous inset vanity, and spent the night imagining myself dropping the replacement medicine cabinet on the sink and somehow breaking the faucet, flooding my downstairs neighbor, and getting evicted. Instead, I taught myself the difference between spackle and joint compound. Over a three-day weekend, I assembled a new cabinet, bought a dozen frames, painted my hallway, replaced the towel rack, and promised no more projects.

For my birthday, I hosted a dinner party. I convinced myself I had scaled it down responsibly because it only involved four courses instead of my traditional seven. Baby steps.

And yet. Change has come in increments.

1. In January of last year, I began writing Morning Pages, a practice described by Julia Cameron in her book “The Artist’s Way.” The method is simple: get a notebook and write three pages, longhand, first thing in the morning. Don’t stop, don’t edit, just stream-of-conscious till you’re done. I don’t know what size Cameron had in mind, but I bought a standard 8.24” x 5.24”, 144-page lay-flat notebook from Denik. 144, being divisible by 3, I finish a notebook every 48 days. Over the last 16 months I can count the days I’ve forgotten on one hand—and I’ve only ever forgotten, never intentionally passed. The most immediate benefit of daily journaling is that it made me confront my obsessive thoughts. It’s simply exhausting to write about the same thing for more than a week or two at a time. More than a vent of daily frustrations, it’s also a carbon monoxide alert for the silent killers in my life.

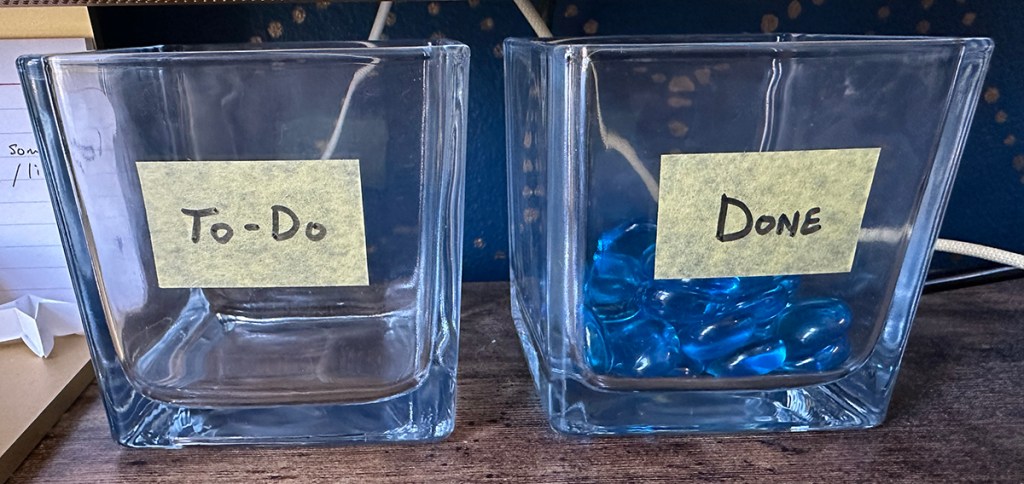

2. When last April’s fever dream broke, Morning Pages prompted me toward a solution to stabilize my work life balance: I walked into Michaels and bought a canister of blue, glass pebbles—the type you might see in flower arranging—and two small, square containers. I labeled one of my jars “to do” and the other “done.” I then counted out the number of blue pebbles representing the hours of work I had to accomplish in a week and dumped them into the “to do” jar. Since then, my work has changed. My job is now to move blue pebbles from one jar into the other jar. More than anything, the focus on moving pebbles has broken many delusions about exactly how much can actually be accomplished in an hour. Time and energy are finite. Leaning too heavily on bursts of hyper-focus is a recipe for burn out.

3. Early in 2024, I set myself two missions for the year. Mission One: Go the Fuck to Sleep. Mission Two: Work the Fuck Out. It took the first half of the year to shake late night work habits, but by the fall I had spun some wheels and ultimately ground out on Mission Two. Finally, I got myself a gym membership because my smart watch told me I was going to die if I didn’t improve my cardiovascular fitness. Fair enough. The gym I chose was close enough to my apartment I that I could roll out of bed at 6:45 and still make a 7am yoga class. Turns out that the benefit of group classes is you can’t get distracted on your phone in between sets. Workouts began and ended in an hour. Once Yoga felt easy, so I started a weight class. As one does, I began paying attention to my protein intake, which brought about a reckoning with the spike-and-crash cycle of my carb-and-sugar-heavy diet. I started sleeping more and drinking less—not out of any virtue, but because my body wanted different things.

Working out felt good, but the real learning came when I realized that the sports-induced asthma that I’d struggled with for my adolescence and early adulthood had quietly vanished. Suddenly, I could breathe while exercising—no band of fire tightening around my lungs, no constricted airways, no hours of recovery afterwards where my whole body felt sapped of strength. The heart monitor on my watch also gave me real feedback on how hard I was working out, which is how I discovered that all those times I felt like I was “wimping out” for “giving up” because I was “tired” were actually times when my heart rate was up to 185bpm.

In short: my mind is very bad at understanding what I am physically, emotionally, or mentally capable of. If my body did not have literal physical self-protective instincts hard-coded into its operating system, I would kill myself before I stopped. I mean that in the most literal sense possible. For years, I was used to working my body until I triggered an asthma attack—and still not stopping until someone else told me to. Asked to perform creatively, and my mind will create a plan as if constraints such as “need for sleep” or “literal number of hours in a day” are negotiable social constructs.

There’s a moment in The Great Gatsby that has stuck with me for years. It’s at Gatsby’s funeral (spoiler), when his father pulls out a crumpled piece of paper to show Nick. It’s young Gatsby’s attempt at a self-improvement schedule:

I used to half-ironically write “Gatsby improvement plans” for myself, fully aware that this was not the lesson I was intended to take away from the book. One of them involved a 5am wakeup time that I maintained for two weeks during a grim period of post-college unemployment. Another mapped out a plan to complete a Masters program, learn four languages, and write three novels in a three-year period.

This year, my ambitions have shifted from “become a genius author in two years’ time” to “not ending up shot to death in the swimming pool of my extravagant mansion.” To that end, I’ve embraced a new motto.

That which can be done, will be done.

It goes like this: trust yourself to know when you need to rest. Believe that whatever you were able to accomplish in a week was all you were able to accomplish. Write your list of to-dos, and if you only finish the first item, accept that that was all you could do with your time and energy. Respect your capacity when it tells you that you don’t have the energy to deal with that person demanding your attention. Listen to the drop in your stomach when someone asks a favor you can’t fulfill. Cut the self-flagellation, the relentless put-downs, the do-or-die mentality because your mind will kill you.

Because here’s the predictable outcome, the obvious reward that you earn after you stop chasing it down: you’ll get more done. Seriously and for shit. I’m at the gym nearly every day. I’m getting close to eight hours of sleep rather than subsisting on a generous six. I published zero blog posts in 2024, and this is my second of 2025. Hardly breaking records here, but goddamn: I’m enjoying the process again.

It almost makes me angry. I wish I could tell you that I became happier by doing less. But really, I became happier by lowering my expectations—and then exceeding them. Instead of meticulously curating a schedule that left no room for downtime, I cleared my schedule until I had room to feel bored—and that gave me the freedom to start filling it with things that brought me joy.

I’d love to write more about those things that are giving me joy. I have a lot of thoughts. But I’m making no promises. What can be done, will be done.

You must be logged in to post a comment.